another 10 to bring them

up.

To make certain that the time underwater

would be used to the fullest, every scene was

first diagrammed on a blackboard and then

rehearsed "dry," either on the boat or on

land, until cast and crew alike knew each

gesture and each step that would be made.

The burial sequence, which required 42 men

in the water simultaneously, took two days to

plan and three days to shoot.

Certain underwater sequences, however,

had to be shot under very controlled condi-

tions in a studio tank. Accordingly, Stage #3

was constructed at Disney's Burbank studios.

The stage houses an enormous 90' X 165'

tank, which ranges in depth from three to 12

feet.

Nemo's "Nautilus"

The design of the Nautilus, itself, however,

proved to be one of the most interesting.

challenges of the movie. "Jules Verne," ex-

plains Goff, "while foreseeing brilliantly the

atomic submarine of today, did not at that

time invent the periscope, the torpedo tube or

sonar. He did not prophesy closed-circuit

television. "

In a way, it was the personality of Nemo

that determined a good deal of the design.

"According to Verne," Goff continues, "if

Nemo wanted to see what was happening on

the surface, he simply poked the glass ports of

the wheel house out of the depths and took a

direct look. Nor would it have been true to

Captain Nemo's nature to skulk along and

fire an armed torpedo at his enemy. He risked

his vessel and himself and crew by ramming

the enemy at frightening speed. If he wanted

to study the marvels of life beneath the sur-

face, he reclined in his elegant bay window

lounge and passed the hours studying the

marine life outside of his luxurious salon.

These items dictated much of the direction of

my design."

Faithful to the book, the main lounge of |

Captain Nemo introduces

such undersea delicacies as filet of seasnake, unborn octopus. |

the Nautilus had to contain a

pipe organ, a

library, rare paintings, comfortable sofas and

chairs, aquariums filled with unusual fish and

soft carpets. Though some of the furnishings

were built in the Disney shops, many of the

pieces of furniture and set dressings came

from local antique shops. Sometimes the

hunt for Victorian furnishings for the sub-

marine brought startled looks of wonder

from the shop owners. Goff explains: "At

the time, I owned my own boat. One Sunday

afternoon I went browsing through antique

stores with my wife instead of going out on

my boat. It seemed appropriate to be looking

for Captain Nemo's set dressings, while wear-

ing my captain's cap. One shop had these

bronze dolphins on display. I called my wife

over to look at them. 'What would you do

|

with them?' she asked. 'For my

submarine

... ' I said. 'You know, when you walk

around the edge where the big davenport is by

the viewport? Well, I need something right at

the edge that you can put your hand on or a

chain across. And if I need it for the viewport

on the other side, we can make castings of

them!' Well, at that point I happened to look

up-at a number of open-mouthed people

who were listening in gaping wonder to the

explanation of my submarine's furnishings."

The sets for the interior cabins of the

Nautilus were built exactly to scale, with ceil-

ings. Though this technique heightened the il-

lusion of being underwater and added to the

reality of the film, it meant that many of

Nautilus cabins measured a scant 8' x 10'. In-

(continued on page 60)

|

|

|

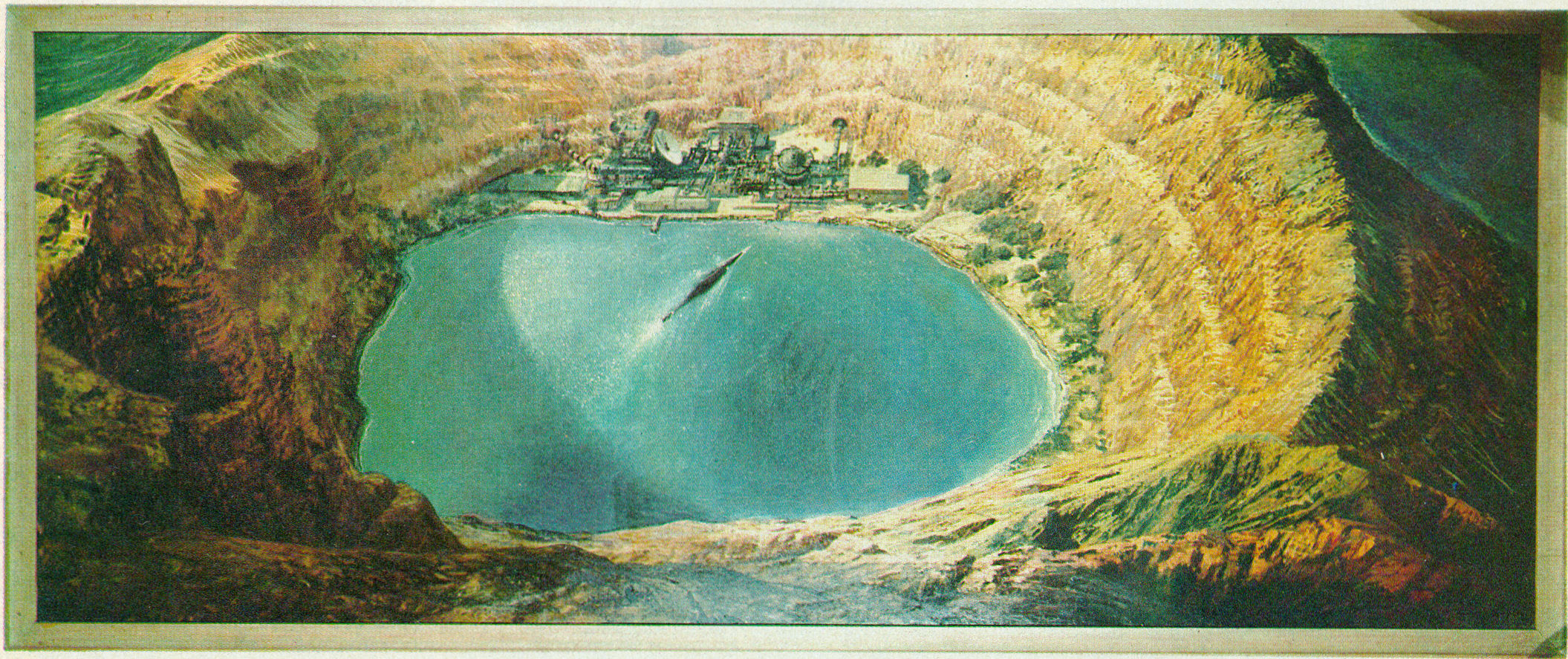

| One of Peter

Ellenshaw's matte paintings for the film. Intended to be used as glass

shots, the paintings are about 8 feet long. |

|

58 STARLOG/February

1980 |

|