|

|

||

|

In the October, 1974, issue of Scale Modeler we ran an article on a rather unique model, the famous Nautilus from Walt Disney's version of Jules Verne's classic 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea. Since the appearance of that article, we have received an unusually high volume of mail on the subject of the Nautilus, many people wanting to know more about the prototype (even though it never really existed) as well as more about the production of the movie. This production was of particular interest to scale modelers as virtually all of the action sequences involved models of one size or another. In response to the many inquiries |

and requests for further information we present this followup article in an effort to tie up some of the loose ends concerning what can only be described as the most famous non- existent ship of all time. Mr. Tom Scherman, a professional model maker for the movie industry, was the maker of the Nautilus fea- tured in the original Scale Modeler article. Since the completion of that model, he has taken his interest to the next logical step. He has com- pleted a second model, this time a cutaway version which shows the full interior layout, something which was left rather vague in the movie. We think you will agree that Mr. |

Scherman's effort is worthy of the highest praise, both in terms of model making and as an exercise in design and interpretation. There was never any such thing as a "com- plete" set of plans for the interior of the Nautilus. An added feature for our readers is a memorandum from the man who was most responsible for the produc- tion of 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea. Mr. Harper Goff was kind enough recently to jot down a few notes pertinent to the production, particularly as it involved models, and we reprint his words here. It was Mr. Goff's genius that was re- sponsible for nearly all of the hard- |

|

|

|

|

ALTHOUGH IT WAS NEVER MADE |

MODEL BY TOM SCHERMAN WITH |

|

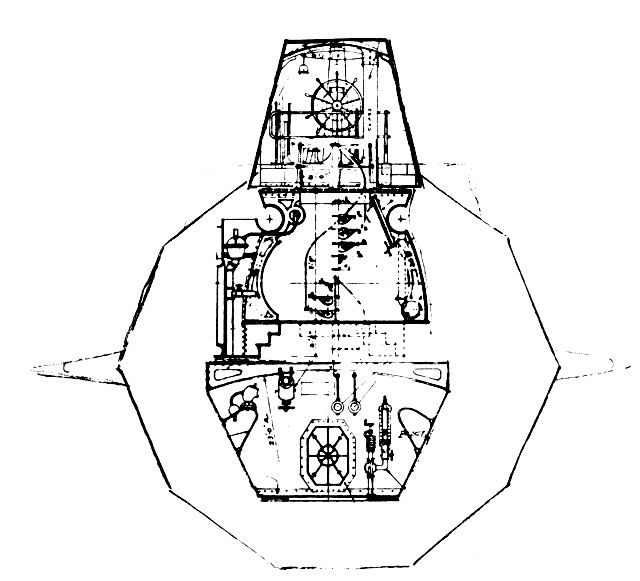

ware and visual effects that met the movie viewer's eye. Following are Mr. Goff's comments: In motion pictures, the text of a classic like this subject is sacrosinct. The 'word' of Jules Verne is not to be made light of, so, the duty of the designer, like myself, was to take the sometimes arbitrary descriptions of the Nautilus as recorded by Verne and "make it work." Jules Verne, while foreseeing bril- liantly the atomic submarine of today, did not at that time invent the peri- scope, the torpedo tube, or sonar. He did not prophesy closed circuit television. According to Verne, if Ne- mo wanted to see what was going on on the surface, he simply poked the glass ports of the conning tower out of the depths and took a direct look. Neither would it have been true to Nemo's nature to skulk along and fire an armed torpedo at his enemy. He prefered to risk his vessel and himself and the lives of his crew by ramming the enemy at frightening speed. If he wanted to study the marvels of life beneath the sea, he reclined in his elegant bay window lounge, and passed the hours study- ing the marine life out side the amazing pressure proof window of his luxurious salon. These items dic- tated much of the direction of my designs. Nemo is quoted by Verne as tell- ing Professor Arronax that, "I need no coal for my bunkers. I have in- stead harnessed the very building blocks of the material universe to heat my boilers and drive this craft." No one can doubt that Verne was making reference to atomic energy. Early reports of the destruction of ships described a so called "sea monster" of terrible speed and tre- mendous power, with great glowing eyes, a great dorsal fin and a tail which churned the sea into a froth when it attacked :its victims which it would ram with such speed that it passed clear through its prey-- usually leaving the broken hulk in two parts. My idea has always been that the shark and the alligator were the most terrifying monsters living in water. I therefore combined the scary eyes of the alligator that can watch you even when the rest of the body is submerged, with the danger- ous pointed nose and menacing dor- sal fin of the shark--together with its sleek streamlining and its dis- tinctive tail. The rough skin of these under- water terrors is well simulated by the riveted iron hull and many |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 1 | 2 |

|

|

||

| 3 | 4 | ||

|

|

||

| 5 | 6 | ||

|

|

||

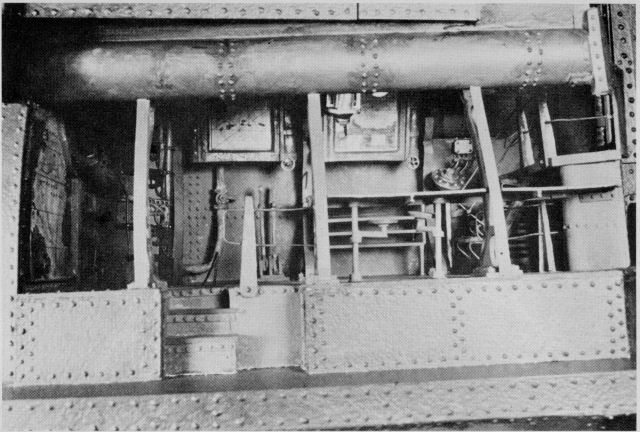

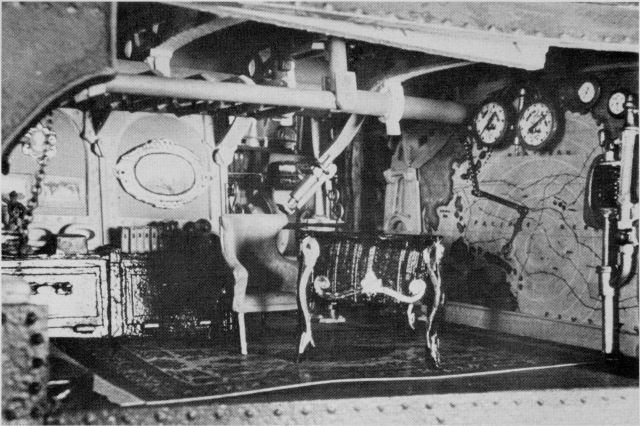

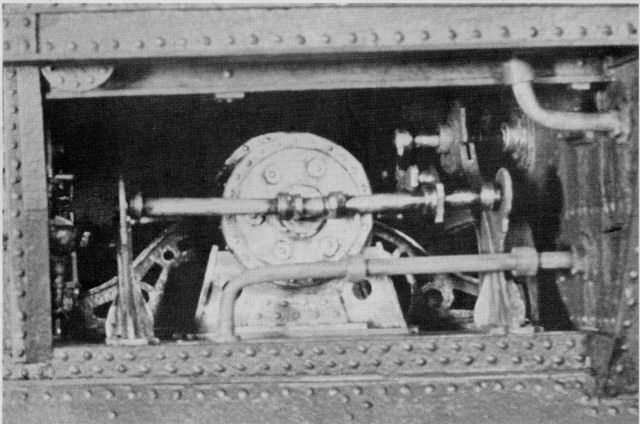

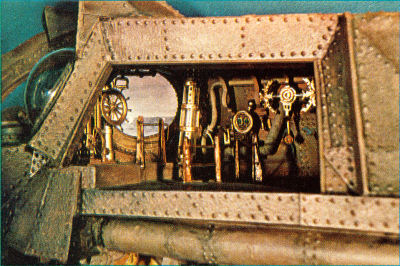

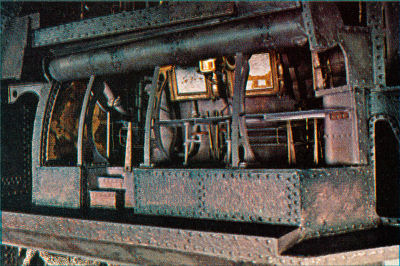

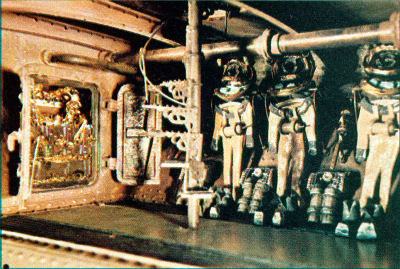

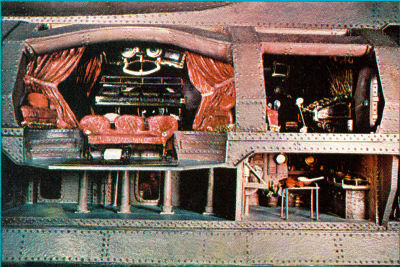

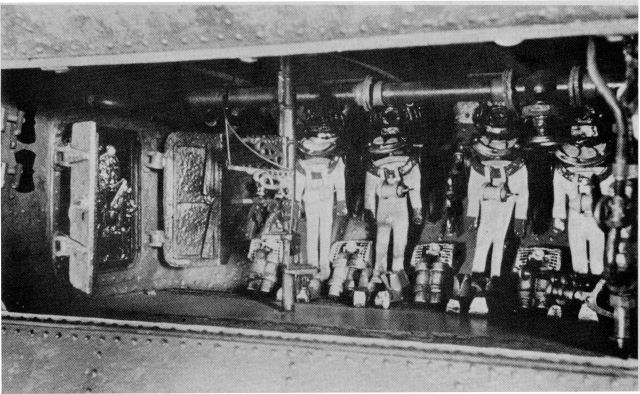

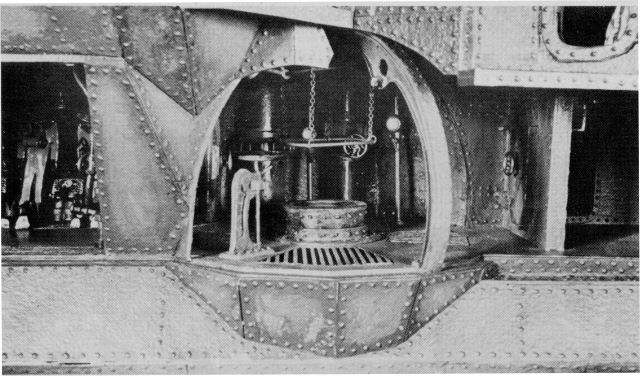

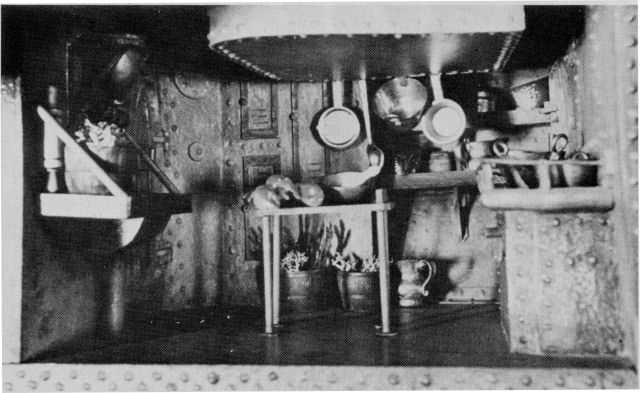

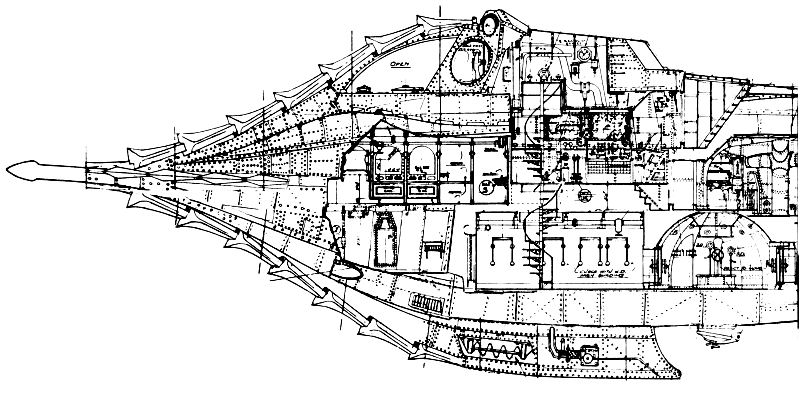

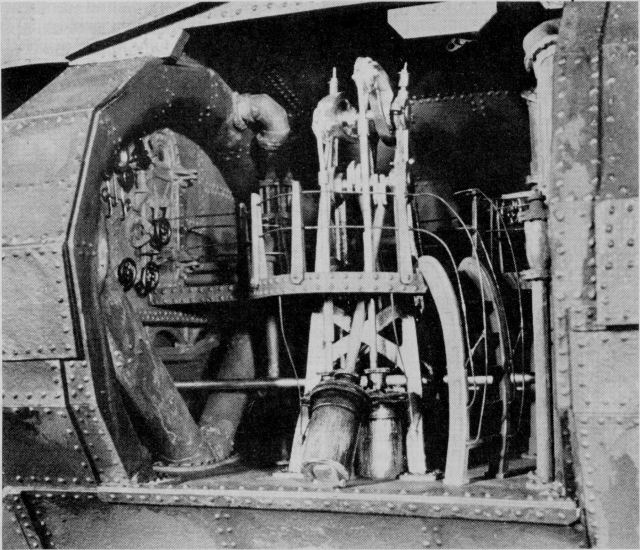

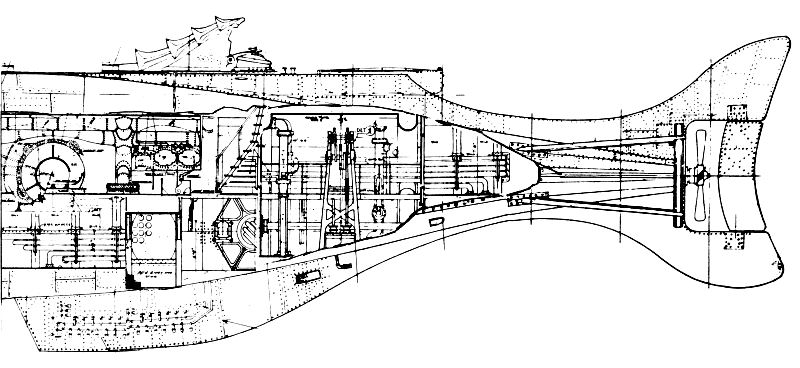

| 1 The Wheelhouse--where the submarine was steered by looking through the view- ing ports at each side of the wheel. Other features include the diving control stancions to the left of the wheel. Along the wall is the atomic counter and trim indicator. 2 Captain Nemo's cabin--mainly used as a private office and laboratory. Taking up an entire wall is a map of the Northern and Southern Pacific Ocean, with the location of his secret hideaway, Vulcania. Also mounted on the chart wall are longitude-latitude indicators, and a panto- graph to monitor the sub's position. |

3 The Chart Room--where Captain Nemo plotted the course. This is the second highest room in the submarine, and it leads off into the passageway, the Salon, and Nemo's own private stateroom-office. 4 Below the Chart Room lies the Outfitting Room where the crew suited up in their diving gear In this room is also the treasure ballast locker at which Ned Land resolves "I could sure lighten this ship." Captain Nemo states the only use he had for such baubles, although treasured in the material surface world, are here aboard the NAUTILUS mere |

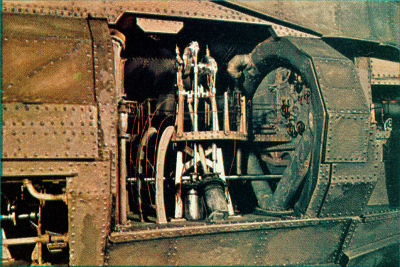

ballast, to keep the ship on

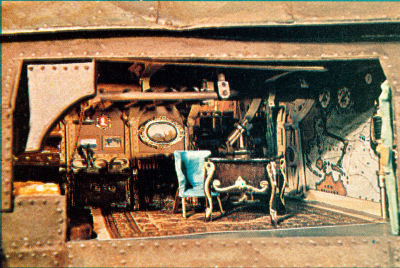

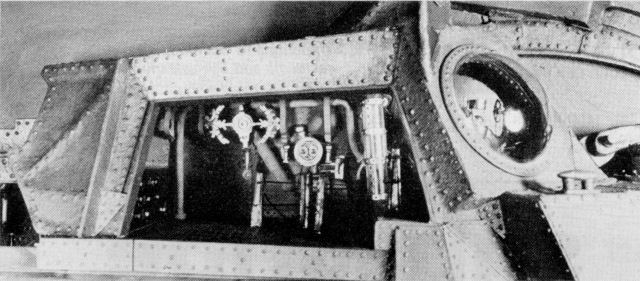

an even keel. 5 The Salon--here Captain Nemo enter- tained his prisoner-guests at the gold pipe organ. Around this room are part of his extensive library and specimens of deep sea life. 6 The Pump Room--here, powerful beam- stroke engines forced water from the ballast tanks, enabling the NAUTILUS to submerge and surface at will. Through the Pump Room runs the power shaft to the stern of the submarine, setting in motion a series of generators and gears for "collision-speed" ramming. |

|

|

|

|

protuberances of the Nautilus. Be- cause the Nautilus drove its way clean through its victim, I incor- porated a protecting and lethal saw toothed spline that started forward at the bulb of the ram and slid around all outjutting structures on the hull. These included the conning tower, the diving planes and the great helical propeller at the stern. |

At the time Captain Nemo con- structed the Nautilus on Mysterious Island, the iron-riveted ship was the last word in marine construction. I have always thought rivet patterns were beautiful. I wanted no slick shelled moon ship to transport Cap- tain Nemo through the emerald deep and so I fought and somehow got my way. (Editor's note: This state- |

ment is in

reference to the fact that the executives at Disney Studios, in- cluding Walt Disney himself, were in favor of a submarine of a very futuristic design complete with a smooth skin and a cigar shape--a concept that would have placed the Nautilus completely out of context with its time.) One of the most awe inspiring iron structures in the world is the cantilevered bridge across the Firth of Forth in Scotland. One of the world's greatest railroad bridges, it was constructed of giant tapered iron tubular columns and trusses. This was the latest word in structural construction of the period in which the voyage supposedly took place so I designed the tubular skeleton of the Nautilus with similar "unions" joining the tubes, just as Nemo might have done, and provided that the upper spaces in this hollow structural frame should be used to store the air while the lower voids would be water ballast. An interesting se- quence in the film in which this is all explained to Arronax by Nemo was eliminated as too time consum- ing. Alas. In 1930 in Portland, Oregon, the old Spanish American War battleship USS Oregon lay at her berth near one of the Portland bridges. It was built in the 1890s and was rich in silhoutte and interest. But it was below decks that she really excelled. In the offi- cer's cabins and the ward room, loving cabinet makers had fitted the most wonderful built-in beds, closets, lockers and chart tables that one could imagine. This elegant wood- work, highly varnished and with polished brass hinges and pulls and rails, was tastefully married with the curves and cambers of the riveted iron ship that surrounded all. The city of Portland gave this treasure to Uncle Sam for scrap during World War II. I tried to carry this exciting interior treatment throughout the Nautilus. The barometer, speed and pressure gauges, the binnacle, were jewel-like as well as useful. Mr. Scherman's model shows this effect well. About the interior design, it is not sound economics to study and design obviously unnecessary parts of a ship if they will not appear on the screen. For instance, the crew's quarters were not accounted for. However, a great deal of attention was paid to the relationship of one compartment in the Nautilus to another. Often in an effort to edit the deadwood from an episode in a film as written and shot, one loses the transitional foot- age which has no other value than to clarify the geography and layout of the interior. |

|

||

|

||

|

||

|

|

|

The cutaway NAUTILUS model is built of wood, celastic, sculpey clay, PVC plastic tubing, and several grades of cardboard. It originally started out to be a sketchy pre-production plan for a more carefully constructed plexiglass and working-metal- parts job, as cardboard eventually gives out in a couple of years. The compart- ments were built individually, at 1/2-inch scale, directly off bluelines of the official studio set plans. To help in pre-production planning as far as what scenes would take place where, this rough room plan of the NAU- TILUS was developed by Disney artists. Copyright Walt Disney Productions. |

|

|

|

||

|

concave blue backdrop just beyond the window outside, a simulated rip- pling underwater effect was thus achieved. Some rooms had to be left out (Ned Land's Cabin, the Arsenal and "Glory Hole" where Ned was placed under guard and locked up), while others were invented--The Crew's Quarters, The Reactor Control Room, and the Engine Room, just ahead of the Pump Room. This became one of the most interesting facets of the sub in that period of history (1860- 1870), for it was modeled after the designs of the engine in Ericcson's Monitor of Civil War fame. Sculpey and polyform clay were used for the arched tubular iron con- struction in the Salon and Pump Room. The straight tubular iron mem- bers were 3/4" and 1" pinewood dowels. The rivets were added with the same system as on the plexiglass sub, except this time white glue was used, applied with a toothpick. A rough, scaly rusted iron texture was needed for the walls. Rather than apply that texture later in the paint job, "pebble-board," which is chiefly used for inexpensive picture matting, was utilized. The floors were of a smoother, thicker cardboard, rigid enough to maintain its own flat- ness without warping, but for accur- acy's sake they were reinforced just to be on the safe side. The total time of this model, tak- ing into consideration the hours spent when first started in 1970 and re- sumed in 1974, came out to roughly 4 1/2 to 5 months. |

|

|

MOST OF THE scenes shot in "20,000 Leagues Under the Sea" fa- vored views of each of the compart- ments as seen from the port side. It did not seem expedient then, to build a complete cutaway with a fully de- tailed starboard outer hull. Thus this concave-convex model, a sort of bas relief of the Nautilus was constructed. To achieve this the builder ob- tained a 30 inch by 9 foot stage flat from work, calculated how much area the rooms would take up (almost 7 1/2 feet worth!), and cut out a rec- tangular hole accordingly. Next, a narrow shelf was attached along the bottom edge of the rectangle. Upon this was placed the rooms in the lowest part of the submarine--The Outfitting Room and Diving Chamber, passageways opening on to the Crew's Quarters and ladder, Galley and Engine Room. Next was the Pump Room, which took up 2 levels in the ship. Lastly (and in its logical position for the safety of everyone |

on board) came the Power Supply Room. Then came the upper compart- ments, some of which had to be cut to fit the contours of the submarine. The gaps, spaces between the rooms were filled in with a fanciful geometric-type riveted plates, done very much in the style of the between-room architecture of the "20,000 Leagues" exhibit at Disney- land. The exterior skin, or the part repre- senting the outside hull of the sub, was made of cardboard reinforced with an almost defunct material called celastic, a plastic treated fabric. 12 volt lamps were next installed, and twinkling Christmas lights were fitted behind the multi-colored glass ports of the Power Supply Room, to give off the illusion of a 19th century atomic reactor in action. Behind the Salon window was placed a revolving disc of rippled glass and a high in- tensity lamp. Properly focused on a |

|